In a field fraught with controversy, a new report sheds light on the multifaceted impacts of oil crops, revealing that the issues at stake are more nuanced than previously understood. Produced by Borneo Futures, which hosts the IUCN Oil Crops Task Force, the report aims to provide clarity on the role of oil crops in biodiversity loss, human rights, and nutrition.

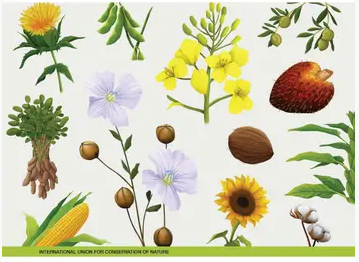

Oil crops, which cover 37% of global cropland, are at the heart of ongoing debates due to their significant environmental and social implications. While these crops are vital for global income and nutrition, they are also associated with severe biodiversity loss and human rights violations. The report comes at a crucial time, with global demand for vegetable oil expected to reach 288 million tons by 2050, highlighting the urgent need for sustainable production practices.

The report emphasises that all oil crops, including those often perceived as less problematic like olive and coconut, can have detrimental effects if not managed properly. Rather than targeting specific crops as villains, the focus should shift towards improving production practices to mitigate their negative impacts.

Professor Erik Meijaard, lead author of the report and co-chair of the IUCN Oil Crops Task Force, argues that positive outcomes are achievable with any oil crop if approached with the right strategies. “What this report shows is that positive outcomes can be achieved with all oil crops. With the right investment, planning, policies, and improved crop production methods, oil crop areas can offer substantial opportunities for reducing biodiversity loss, addressing human rights issues, and restoring nature,” he stated.

The report uses oil palm as a case study to illustrate how the context of cultivation can drastically alter its impact. In contrast to monoculture oil palm plantations that replace biodiverse forests in Asia, oil palm managed within African forests and village gardens demonstrates a more sustainable approach. “It is not the palm, but the context in which it is grown, that determines the impacts,” Meijaard explained.

Malika Virah-Sawmy, co-chair of the IUCN Oil Crops Task Force, criticises the oversimplified view that certain oil crops are inherently good or bad. She calls for a shift in focus from demonising individual crops to improving production practices and addressing systemic issues.

The report unveils some surprising insights, such as the potential of current maize and coconut cultivation areas to reduce extinction risks for threatened species. However, it also highlights the challenges posed by the concentration of power in the global grain trade, where a few companies control up to 95% of the market. This concentration complicates efforts towards more equitable agricultural practices.

While well-documented impacts are associated with crops like oil palm and soybean, others such as peanuts and sesame are less studied but also linked to environmental and human rights issues. This gap in research underscores the need for more comprehensive data to inform public discussions and policy decisions.

Professor Douglas Sheil, another author of the report, emphasises the importance of focusing on how crops are grown, traded, and consumed rather than just what is planted. “We need to shift the focus from what’s planted to how it’s grown, traded, marketed, and consumed. This report is our first attempt to overview practices, impacts, and standards and what can be done,” he said.

As the global oil market continues to grow, understanding the complexities of production is vital for making sustainable choices. The report aims to bridge gaps in knowledge and encourage further research to address remaining blind spots.

For those concerned about the environmental and social impacts of vegetable oil production, the report offers a comprehensive overview and encourages informed decision-making. The report is available for free download, providing valuable insights into the complex world of oil crops and their role in shaping a sustainable future.